By Carmelle Javney Mohr (Long-inspired by Jonathan O’Donohue, Bayo Akomolafe, Wendell Berry, Mary Oliver, Rumi, Rilke, Frost, and Farley Mowat‘s wolves)

A two-part piece spoken Oct. 10, 2015 at the Celebration of Life for Lorraine Kasube Mohr. It is originally-formed and intended as spoken-word, however a written-script appears here. Part I is interwoven words of Carmelle Mohr and Parker Palmer in tapestry; Part II, by Carmelle Mohr. For the possibility that the one, wild and wonderful life of Lorraine Mohr (and Mark Chytracek) may continue bringing beauty into being, this piece is here offered unto the public sphere.

—

Autumn is a season of exhilarating beauty. It is also though, the steady decline, a deepening melancholy. The days become shorter and colder, the trees shed their glory, summer’s abundance decays into winter’s still. Initial delight in the autumnal colours that burst forth as Summer Falls each year – the beauty evoked in front of our eyes when Season eclipses Season! – can easily disintegrate into a sadness. Nature’s golden-leafed carpet, magnificently lain before us to walk forth into the day upon is beautiful… But, all this beauty is the fading away of life once vivacious and strong; keen-youth that was once unyeilding in the wind. All is dying. Even amidst the shimmering gold and crystal-sapphire backdrop skies, it is easy to allow the prospect of death to shadow all that Fall is also.

There is a simple fact though: all the ‘falling’ is also full of promise. The theology of Compost no? Seeds are planting in moist earth, leaves are composting. This death is Earth preparing for an uprising of green. Yet again.

As I weather the autumns in my life, nature is a trustworthy guide. We humans easily affix our gaze upon the falling; upon that which goes to ground. The decline of physical strength; the disintegration of a relationship; the diminishment of joy; the loss of a beloved. But just as autumn seeds the earth, life’s harshness seeds us too. In each experience of loss something is indeed dying. Yet, also, deep, amid the falling, silently, lavishly, seeds of new life are being sown.

Are the sensuous glories of autumn but not the grand affirmation that new life is hidden in dying! Yet whom of us paints deathbed scenes with the vibrant and vital palette nature uses? When we fear death, fix our gaze upon that which is parting, beyond our control into a space beyond our ability to ‘prove,’ we blind ourselves to the grace Death possesses.

However if this is Nature’s testimony, how can it be fathomed? Dying is devastating, yet, say you, also the container of beauty? In the unimaginable that sisters and brothers around the world suffer, in disease such as dementia, as Alzheimer’s, as depression, or suddenly extinguished life – how dare there be beauty within such pain?!

However if this is Nature’s testimony, how can it be fathomed? Dying is devastating, yet, say you, also the container of beauty? In the unimaginable that sisters and brothers around the world suffer, in disease such as dementia, as Alzheimer’s, as depression, or suddenly extinguished life – how dare there be beauty within such pain?!

Yet how dare there not be.

Once again, I find Nature a trustworthy guide. In the Natural World, diminishment and beauty, darkness and light, death and life are not opposites. They are paradox. When held together they reveal that in all things there is a ‘hidden wholeness.’ Even and especially in suffering, trauma, death.  In a paradox, opposites do not negate each other, they co-create in mysterious unity; the mysterious unity which is the grace of the world. A mystery that defies modern conceptualization. But one that is, surely, the heart of reality.

In a paradox, opposites do not negate each other, they co-create in mysterious unity; the mysterious unity which is the grace of the world. A mystery that defies modern conceptualization. But one that is, surely, the heart of reality.

Of course we prefer the ease of either/or to the complexities of both/and so we have a hard time holding opposites together. We want light without darkness, the glories of spring without

the demands of winter, the pleasures of life without the pangs of death. But neither just light, nor just darkness can truly enliven us. On their own without their counter-part neither can sustain us in hard times. When I reject the inevitable diminishment of summer, when we so fear death, the result is artificial light that is glaring and graceless. The moment we say ‘yes’ to both however and they join in paradoxical dance, the two make us whole. Life conquers death. And faith is a cascade.

I shall always grieve when beauty goes to ground. But Autumn is also for celebration. Autumn is also Thanksgiving for the primal power that promises to make all things new, desde siempre hasta siempre. When I give myself over to this organic reality – to the endless interplay of darkness and light, falling and rising, grandmother and granddaughter – I am given a life as meaningful and whole as this graced and graceful world and the seasonal cycles that make it so.

—

Lorraine Honey Kasube Mohr is my grandmother. I am her youngest grandchild. She was my main reason for returning to this part of the prairie about seven years ago. Over the course of those years, I departed and returned to her side from different corners of the world, and she began a gentle stroll back into the past.

Honey’s memory was impeccably sharp don’t you know. To the final day Honey remembered how to write in shorthand and not too long ago would’ve delighted and delivered at the request to recite each school teacher and president she ever had. Walking through the sequential doorways of Past though, meant that Honey gradually forgot me as her granddaughter. And so in the last 6 years together, Honey and I have held a different relationship, ushered into a rather strange place – one that refuses the characteristic earmarks of location and fixity, colour and time. The place we shared was hard to be in. Yet, also, as her memories faded like little passings along the way, a new beauty appeared in each. I want to tell you a bit about that beauty. I also had the honour of walking Lorraine out as she stepped unto the horizon, and want you to share this peace.

Lorraine fell asleep in a wash of blue. Her room like her wardrobe like her eyes were gentle, calm, blue arctic skies. Blue was her multimedia canvas. “5 foot 2,” she’d say proudly… “eyes of blue.” In robes of this wondrous colour, she walked from this world. Royal, indeed.

The first hour of her last day was a starry night. Silent night. I was cycling back after the quickest breath away under a deep navy blue, my gaze affixed to be by her side. As I parked my bike, I glanced sky-ward, from habit not conscious. My breath was stolen – stars were brightening like I’d never seen before. And countless are the times I’ve gazed into this canvas, drifted asleep in canoe underneath it, painted futures of world peace into the endless navy. Yet the stars were brightening like I’d never before known. The Prairie’s Nightcloak, if you’ve not yet met, is embroidered in milk way and Orion cowboy belt. This night, it shone at its finest. Each star pin-pricked through, like windows into the realm, shh! just beyond! Then, a warm breeze came arushing down the road, like upon a bending river. Through rock and mortar, it rushed through without passing glance, as

though this built landscape truly was but 17 years old in a land of Ever. They were drawing near. Ancestors and beloveds-gone-before. They were coming. Coming to welcome the way of the Lord.

Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, are cruelest ways to pass from this world. As the grandchild forgotten many moons ago, I’ve tasted an ounce of the suffering this illness unleashes, silently. Any who’ve witnessed a beloved endure it would unreservedly give our lives if it but could save another from it. Alas.

Its common trait is the disintegration of a person’s social graces: of kindness, compassion, gentleness. In other words, all that was Honey. We offer utmost thanks however for here Honey was anomaly. To the final hour, she was the sweetest, kindest, generous person you have ever met. Six grandchildren bet their lives on this claim.

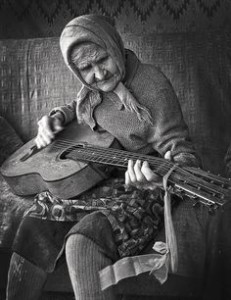

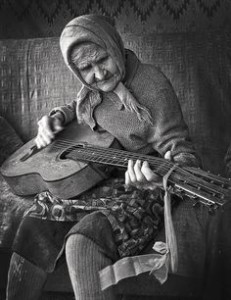

Sometimes though – because I was a bit of an unstickable in her mind – Honey didn’t always don her Sunday best in my presence if you know what I mean. The harshness of these moments were dark. They were also, though, where I came to see something I’d never before been able to. All these years, underneath the role in which she and others donned her entirely – ‘Servant’… was a strong, unique, sovereign, and unpredictable woman. Her proper person. Lorraine the softball pitcher; Lorraine the quick wit; Lorraine the valedictorian; Lorraine the remarkable shot spitting water through her teeth; Lorraine the woman who sided with the meekest no matter the social consequence. In these slips of graciousness, or slips of ‘Honey-ness,’ Lorraine Mohr was a fearsome, wondrous beauty to behold.

The Fall in Camrose has been prolonged, lasting. Too lasting. So too was Honey’s passing. In some ways 10 years long. This summer’s abundant sun soaked deeply into the soil. Today, these summer rays live anew in the hues of gold and green and brown that shimmer this landscape. So too, Honey’s love abundant, soaked deeply into this place, into you and I, this community, this Earth. So too, as she fell away, beauty was brought into being anew.

As I began to disappear from Honey’s memory as her “granddaughter,” she as my “Grandmother” disappeared too. Up till then these had been the names by which we’d known each other. Now though they simply no longer made sense. So it was time to uncover new ones by which we’d know each other, flipping the page, hand upon hand, into the next chapter together.

So I became her “young friend,” and she became my “old friend.” A year or so later, I’d become her “daughter-in-law,” so she became my “mother-in-law.” Eventually, each visit was a ‘first’ visit, so these names fell away too. Now I had become “Stranger.” So she became “Stranger” too. But strangers merely awaiting a meeting to be friends. We got to meet each other many times.

In the final chapter of Honey’s story, our bodies, if they could be names, fell away too. For now we were and forever shall be two souls accompanying each other. Our bodies in static chairs but spirits alive in adventurous story.

The memories that in many ways make Honey Honey, that make Mom Mom, that make Lorraine Lorraine, slowly faded and for this we have been grieving and hating for 10 years. But in each passing falling memory, Honey also arose. Anew. The grace of this world – that in which Honey’s faith ne’er failed – never let one chapter of Honey’s story end with death. Instead each time she was undressed from her stories, she put on more of the Holy story; the story that binds all as one family of one Place. Each falling leaf was the becoming of sacred. And so in the final moments I tell you, Lorraine became an angel. Actually.

To be the grandchild of Lorraine Mohr is to be blessed and humbled by a generosity of love so abundant, unreserved, outpoured… That one might have something to offer her, (as though something were absent) is not a thought the mind can imagine. Lorraine fell away from this world in peace though and I want you to know that, for I can tell you that. I’ve sailed the Ship into the horizon and stepped ashore where death and life eternal kiss. Where the gold sun sets. So, I’d like you to know that throughout the final days and final breaths, I could tell Lorraine that it would be okay. That it is beautiful there. That we would be okay.

And so heads resting on pillow together, we breathed in and out, looking up through the mortar into the night’s canvas beyond. The clock chimed 8:30pm. Her and Papa’s soundtrack. A warm breeze entered the room. Randy took his place by her side. Brother George next, then Sister Ethel, Arlene, Mother Minnie, Daughter Christine, and others whose faces are not for my knowing. Just beyond, a chorus began, softly. ‘Gloria, gloria…’

Lorraine breathed her last in gentleness which is what she was in this world, and always shall be.

Thanks Be for our little blue sister. May we be her living memory now; a light in the dark.

—

However if this is Nature’s testimony, how can it be fathomed? Dying is devastating, yet, say you, also the container of beauty? In the unimaginable that sisters and brothers around the world suffer, in disease such as dementia, as Alzheimer’s, as depression, or suddenly extinguished life – how dare there be beauty within such pain?!

However if this is Nature’s testimony, how can it be fathomed? Dying is devastating, yet, say you, also the container of beauty? In the unimaginable that sisters and brothers around the world suffer, in disease such as dementia, as Alzheimer’s, as depression, or suddenly extinguished life – how dare there be beauty within such pain?! In a paradox, opposites do not negate each other, they co-create in mysterious unity; the mysterious unity which is the grace of the world. A mystery that defies modern conceptualization. But one that is, surely, the heart of reality.

In a paradox, opposites do not negate each other, they co-create in mysterious unity; the mysterious unity which is the grace of the world. A mystery that defies modern conceptualization. But one that is, surely, the heart of reality.